Welcome

....to JusticeGhana Group

JusticeGhana is a Non-Governmental [and-not-for- profit] Organization (NGO) with a strong belief in Justice, Security and Progress....” More Details

Zimbabwean author NoViolet Bulawayo: 'I like to write from the bone'

Zimbabwean author NoViolet Bulawayo: 'I like to write from the bone'

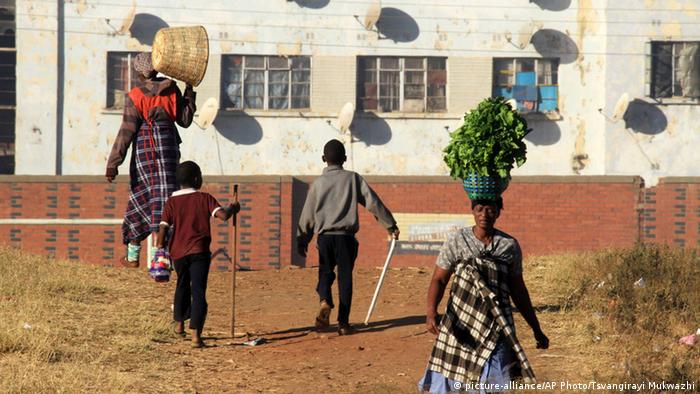

Writing about Zimbabwe while living in the US has changed her language and her identity, says NoViolet Bulawayo, the author of "We Need New Names." DW met up with the young African writer on her first visit to Germany.

Ms. Bulawayo, you teach fiction at Stanford University. How do your colleagues and students address you?

NoViolet. That's the name I go by. Elizabeth Tshele, even though it's my birth name, is the name that is just in my official documents. I like to remind people that I come from a culture where you grow up with quite a bunch of names.

Why did you choose this name, NoViolet Bulawayo?

It's from my mother's name, actually. My mother was named Violet. She passed away when I was 18 months old, and she wasn't really spoken about that much. I grew up with a sense of something missing. I decided when I was at a certain age to honor her. "No" in my language means "with." Of course Bulawayo is my city, my hometown. And being in the US for about 13 years without being able to go home made me very homesick. So it was my way of staying connected.

Why do we need new names?

I wrote the novel at a specific time of my country's history. Recent history, I should say, when the country was coming undone, due to failure of leadership. And by saying "we need new names" I was speaking for the need for us as a people to sort of re-imagine, rethink ourselves, rethink our way, think about where we were going. We needed new ways of seeing things, new ways of doing things, new leadership. It was basically a call for renewal. But it should not be confined to Zimbabwe. I believe you can translate across borders.

Many readers think your novel "We Need New Names" is strongly autobiographical. Or is it not?

Not as much as most people think. There are parts of me as in most of my work. I like to write from the bone. Even if it's just a small part I feel like it gives my work the certain charge. The first half of the novel does not have much of me. Darling, the narrator and main protagonist in Zimbabwe, does not have a strong connection with me. My childhood was very normal and beautiful. Zimbabwe in the 80s was this land of promise. We grew up as kids in working countries grow up - because the country at that time was really functional.

But as Darling does not know the stability my generation enjoyed and experienced, her childhood is really under pressure. So it is when she crosses the border to the US that our stories started to sort of intersect. I actually allowed her to borrow from mine, because I kind of know what it is like to be an outsider. To be an immigrant, to struggle with fitting in, find my way in a new space. But even in that part of the novel I didn't set out to write an autobiographical text. The language you chose for your protagonists, the children who live in Paradise, is a mixture of African and English vocabulary, neologisms, incantations, curses. How did you find this strong and colorful language?

I'd say I'm indebted to my culture. I grew up in a space where language was alive. Language was currency. I wanted to write a book that captured that, that would resonate especially with readers coming from that space. And a part of it also came from the fact that I was raised by storytellers, especially my father and my grandmother, of course the women who stayed home when I was growing up, they talked, they gossiped. So I was very conscious of language as a living beast. I wanted the book to be a celebration of that. I wanted that color and that texture and that pulse present.

Is this the language that clearly expresses a mixed, confused identity?

I wouldn't say it's a confused identity. I would say it's an identity that comes from negotiating two cultures. English came to Zimbabwe as with most African countries through colonization.

What language did you grow up with?

I grew up with Ndebele, and then English was there, somewhere, it's a language that we encountered in school. I wouldn't bring English home; my father would not allow it. And looking back now as an adult I think it is a good thing because it cemented my relationship with my language.

Now, when it comes to me writing I'm juggling two languages, obviously, Ndebele is my ancient language, the language of intimacy. And as much as I'm fine with communicating in English it doesn't have that weight for me. But of course I have to produce a book that looks like English on the page. So it takes me back to that point of negotiating. And of course there is the love of language. I really want my language to be in my work. So I come to it through a process of translation.

In the second part of your book, when your protagonist Darling is in the United States, the language is pale, less colorful, and to describe the life she leads you make use of stereotypes and clichés. Is this an expression of that she loses her identity, or part of it?

In the second part of your book, when your protagonist Darling is in the United States, the language is pale, less colorful, and to describe the life she leads you make use of stereotypes and clichés. Is this an expression of that she loses her identity, or part of it?

Whenever somebody crosses geographical spaces, whenever we cross cultures, something is lost. I remember just from my own experience that I spent the first year in the US in silence. I moved from being one of the noisiest kids in class to being the quietest. And I was dealing with all kinds of things, especially culture shock and failure to access the language. So that is exactly what is happening to Darling. Part of her identity is tied to space. So without her language and without the specific group of people she interacts with, she has to become a different person.

And I know readers complain about that, but I feel like they sort of need to think deeper about what's happening to Darling. Language is one way that disconnection kind of manifests itself. And I hear this from immigrants that I meet in the US, even older ones who have been in the US for so many years, that they are struggling with language.

This naturally leads to the question: Are you a Zimbabwean, an African or an American author?

I'm a Zimbabwean author, and by extension I'm an African. So that makes me an African author, just like I'm an African woman. But of course we have to add that Africa is a big monster of space. It's not singular in any way. So as much as we claim some of these identities, they are also not small. When I think about those identities, especially as somebody who is writing outside, I'm thinking in terms of representation, in terms of how important it is for the young generation of would-be writers, the ones who are going to be writers in the next 10, 15 years, to face the fates like mine in a space that has been dominated by other races and other cultures. That's why I'm quite comfortable claiming those identities.

American not so much, I've lived there for 14, 15 years. To begin with, I still don't hold American papers, even though I'm working towards it. So that's one way that kind of puts you in the margins, puts anybody in the margins. It complicates the way that you imagine your identity. I arrived in the US when I was 18 - I spend my very late teens and 20s there. And that has left its fingerprints on who I am.

You mention "Shitty former Rhodesia" and late in the novel "Zim," but you never clearly say that Paradise, the slum the children you write about live in, is in Zimbabwe. Why don't you address Zimbabwe and its political problems or Mugabe directly?

I felt it wasn't necessary. I felt the context was there. We all know that it is Zimbabwe. Part of why I left it like that is it's not specifically a Zimbabwean story. It has happened in a lot of places in the world and is going to happen. So I wanted it to have this kind of universal aspect to it. Sometimes when you name a thing it arrests people's imagination and perceptions.

I'll mention, though, that the first drafts of the novel were actually naming Zimbabwe, and they addressed Mugabe. The draft was not in Darling's voice, it was in an older peasant's voice. So you can imagine it was very political. There was a lot of an angry NoViolet in there. It started to kill the story after a while, and I sort of had to pull back and introduce a young narrator and also take the politics out of it. In this version I think the politics are still there, but this is not blocking the story.

It took you 13 years to be able to return to Zimbabwe. Why so long?

Well, because the life of an immigrant is hard, especially in the West. For me it was a mixture of not to being able to return because I was in school all that time. And then there was also a time when things were unstable in Zimbabwe. Two years after I came, I first had the opportunity to go back, and I was like, well, I'll go in a couple of years, there is no hurry. And then of course in a couple of years things started to go bad and you just didn't know what was going to happen. I kind of stayed away out of uncertainty. And of course your friends and family on the ground would say, just stay there until this country sorts itself out.

So, are things in Zimbabwe sorting themselves out now?

So, are things in Zimbabwe sorting themselves out now?

They are not as desperate as they were when I was writing "We Need New Names." Then we really were at the height of our crises. Now we still have the same government in power but things are quiet - we don't have the violence that characterized especially 2008, 2009. Inflation is sort of stabilized, we are using the US dollar. The complication there is that not everybody is able to get their hands on them. People's wages are really not the greatest, but people are resilient, they are surviving. I'm really inspired and in awe of how people are able to hold it together and try to live regular lives. I don't know how they do it, but it is really not as desperate. It could be better but it is nothing compared to where we are coming from.

Migration is the central theme of your book. You are here in Europe and in Germany for the first time. In these last few months, hundreds of thousands of refugees have tried to leave Africa and cross the Mediterranean or thousands of kilometers of land to come to Europe. Many lost their lives. What do you think or feel when you see reports on this?

It is a saddening and frustrating situation, saddening in the sense that people make the difficult decision to leave and face death - because that is what this trip is. Of course you are looking for greener pastures, but people know that death is part of the equation. The frustration comes from the fact that African governments have failed their people to that extent that they have to make these difficult choices.

Another part of the frustration comes from the fact that the international community has until recently, when the situation got out of hand, done nothing when people could have been helped. There was a time when governments were like, "Hey, you get in the boats - you're on your own." I think it is time we looked at our humanity and realize that the world is really becoming more global. It is time to find a way to help each other. Because the reality is that those people are not going to stop coming. The question is, what do we do?

Date 15.07.2015

Author Interview: Sabine Peschel

Source: Deutsche Welle

A Review of Dr. Obed Asamoah’s Book “The Political History of Ghana (1950 – 2013) – The Experiences of a Non-Conformist.”

A Review of Dr. Obed Asamoah’s Book “The Political History of Ghana (1950 – 2013) – The Experiences of a Non-Conformist.”

BY VALERIE A. SACKEY

This book is a welcome mine of information on matters as diverse as the rise and fall of political parties since pre-independence days, Ghana’s foreign policy over the years, the intricacies of Trans-Volta Togoland affairs and the PNDC years.

Having been in the thick of the action through most of the period covered by the book, Dr. Asamoah is well qualified to share his observations and experiences, which will generate much discussion and debate.

The author, however, has been to so many places that it is sometimes hard to see where he is coming from. He admits in his preface, that he has “vacillated between revolution and multi-party democracy.” I lost count, halfway through the book, of the number of political parties and regimes in which he played some role. He expresses admiration for such odd bedfellows as Marx, Gandhi and Kim Il-Sung. He says, “I shared the visions of Nkrumah, General Acheampong and Rawlings,” which may cause some puzzlement at the inclusion of Acheampong!

I recall sitting in the garden of the French Ambassador, to whose residence I had brought my children to safety whilst Acheampong’s soldiers ransacked my husband’s government bungalow. I was listening to Acheampong’s radio broadcast justifying his coup of the previous day and the only fact which sticks in my mind is his complaint that officers were not provided with decent carpets in their quarters!

The best thing which came out of Acheampong’s “vision” was Operation Feed Yourself, due largely to the energy of Bernasko. The worst was seeing terrified schoolboys being dragged by soldiers from their hiding places under the beds in staff bungalows and being hunted down in the bush around Opoku Ware School. Why were they terrorised? Because they had not shown “respect” when Acheampong and his entourage had driven past the school!

Dr. Asamoah’s book is a veritable omnibus in that it carries a huge variety of solid facts as well as personal perspectives. But a good omnibus, whether real or metaphorical, should run smoothly. If there is some dirt in the petrol tank of a real omnibus, it will drive in a stop-and-start manner. The dirt in the petrol tank of Dr. Asamoah’s omnibus is his rather irritating disregard for chronological order. In one paragraph he may be in 1987 and in the next he is back in 1983 or even 1957. The reader has to keep re-orienting himself in order to piece together the real sequence of events.

I arrived in Ghana in March 1959, a few days after Independence, and was met at the airport and driven to Kumasi by Victor Owusu, a relative of my new in-laws. My knowledge of politics in Ghana was therefore very limited by the anti-Nkrumah opinions which I was fed by my in-laws and at first I was too busy adjusting to a new life, teaching and raising a family, to question what I was told. It took a few years to make my own observations and form my own opinions.

I shall therefore focus my comments on Dr. Asamoah’s book mainly on the period between the mid-1960s and the time when I left public office in 2001.

In mentioning the creation of the Brong Ahafo region by Nkrumah, the author says that “Dr Busia, a Brong, curiously objected” to this. There is nothing curious about it. After Opoku Ware I’s war in the Brong area, the Brong divisional chiefs were sent to Kumasi where they stayed for some years. They were provided with wives of Asante royal blood. Meanwhile the kingmakers of their traditional areas installed new chiefs. When the exiled chiefs finally returned, having assimilated Asante values, they found that they had been replaced. Over the years since then, many traditional areas such as Offuman and Wenchi, Dr. Busia’s hometown, have had conflicts arising from the struggle between two royal families. Dr. Busia was related to the Wenchi royal family which traced itself back to the Kumasi exile. So it was no wonder that he did not want to see a Brong Ahafo region split off from Ashanti.

Dr. Asamoah mentions Nkrumah’s Bui Dam Project which was abandoned for 40 years “until Kufuor came to its resuscitation.” This is not wholly correct. The decision to update all the data on the Bui Dam was taken in the mid-1990s. Under the direct supervision of the then Vice-President, Prof. J.E.A. Mills, a thorough review of project plans was undertaken, including economic, social and environmental scoping. President Kufuor then found that the basic groundwork had been done, enabling him to proceed with the beginning of the actual implementation.

It is worth noting that several other projects for which the NPP has claimed the kudos also benefitted from the designs and studies done by the NDC, for example the Tetteh Quarshie Interchange, the Mallam to Cape Coast road and the National Health Insurance Scheme. It is a pity that the NPP varied the designs to cut costs and hereby created future problems.

The author refers to the burning of books which he says was instigated by the TUC in the period immediately following the 1966 coup. At the time, I was teaching at Opoku Ware School in Kumasi and I was in charge of the school library. An order came that all books by or about Nkrumah and any pictures of him should be removed from school libraries and destroyed. I refused to comply. I heard that General Kotoka was in Kumasi and was staying in a military guesthouse near the Officers Mess. I knocked on the door and he opened it himself. He invited me in and asked why I had come. He was shocked to hear of the order to schools and told me to ignore it. It seems that the people with small minds who seek to obliterate or distort those parts of history which they prefer to ignore, generally do so without the consent or even the knowledge of their leaders.

Dr. Asamoah seems to be genuinely muddled about the events of June 4, 1979. He says, “Flt Lt Rawlings carried out his first coup.” He continues to use the word “coup” in subsequent pages.

Then he says, “An initial move in May 1979 failed.” A move to do what? Certainly not to carry out a coup!

These events can only be understood against the background of the conditions in 1979. “Kalabule” was virtually universal. The people were angry about the shortages and the profiteering and their anger was mainly directed towards anyone in military uniform, thanks to the years of NRC, SMC 1 and SMC II rule. The junior officers and other ranks were angry with their seniors, blaming them for the disrepute into which they had brought the military.

The SMC II, sensing the public antagonism against them, needed a safe exit strategy and had therefore announced a general election to be held in June 1979. Some within the military, who were concerned about restoring the integrity and honour of the Armed Forces, saw an urgent need for the military to purge itself before the scheduled elections in order to restore civilian confidence under an elected government.

Those of this opinion made several attempts to voice their concerns to the commanders during the durbars at the stations, but all the attempts to wake up the senior officers to the frustrations persisting at the time fell on deaf ears and amounted to nothing. This is why in desperation on May 15th Flt Lt Rawlings and a small handful of men, gathered some senior officers by force later that morning to make them listen to their concerns. This was the “move” to which Dr. Asamoah refers. He then refers to the arrest and trial of Rawlings and his men as a “trial for subversion.” This is not the case. A military Court Martial at Burma Camp tried them for the offence of “mutiny”.

Normally, a court martial is an in-house military affair but the SMC II for some reason decided to open proceedings to the press and the public. Presumably they wanted to make a public show of the mutinous group, but they sadly miscalculated. The publicity given to the trial rather aroused public sympathy, not only among the other ranks of the military, but also among workers, students and the general public. It is therefore strange for the author to imply that Rawlings planned to get tried in order to arouse sympathy.

What happened on June 4 was never a coup d’état. It was an uprising of an angry people. It was waiting to happen and the trial of Rawlings and his men was simply a catalyst.

Dr. Asamoah twice refers to the demolition of the Makola market, but only once suggests a reason. He says it was “a warning to hoarders and profiteers.”

The facts are not so simple. The other ranks were angry with their superior officers for creating a situation in which the general public regarded the entire Armed Forces with contempt. But they were also angry with the market women who had spat on them and had emptied their chamber pots over them simply for being in uniform. Chairman Rawlings knew of the prevailing hostility towards the market women and sensed the impending wrath that could befall the women. To allow the ranks to vent their anger without bloodshed he gave an order for the market to be demolished. The order was followed through after market hours to avoid the potential bloodshed should the soldiers accost the market women.

The author glosses over the fact that within a period of just over three months, Rawlings was able to subdue the cries of “let the blood flow” and the random acts of violence committed by some individuals and convert this emotion into a house-cleaning exercise. Also within this period (less than a month after June 4!) general elections went ahead and in September he handed over to the newly elected President Limann. Immediately after the handing over ceremony, Rawlings joined the inauguration parade to resume his role as a soldier. Are these the actions of a power seeker?

There is little doubt that if Limann had been true to what he declared in his inaugural speech to continue the “housecleaning” and pursue probity and accountability, Rawlings would have been content to continue the career which he loved. The new government however, happily shared out contracts among themselves. The requisition books found at Peduase Lodge revealed the mind-boggling quantities of hard liquor ordered for cabinet meetings. Members of the AFRC were got out of the way with tempting payments for studies overseas. Those who refused, including Rawlings, were harassed by Limann’s security services. Dr Asamoah says, “When he (Rawlings) stopped at a garage in Sunyani to fix his car, he was mobbed, thereby raising his appetite for a return to power.”

This comment trivialises what was happening! It takes a very shallow person to think of undertaking a coup just because a crowd applauds him!

What was really going on? What was Rawlings doing in Brong Ahafo? He travelled widely during the Limann years, trying to keep up the spirits of youth groups who were inspired by the aims of June 4 but also who were dismayed to see the government undermining these very principles. He encouraged many of them to establish commercial farms. At times he had to hide from the security forces, sometimes in some very unlikely places. If anything made him turn his mind towards planning a coup it was certainly not the applause of a crowd in Sunyani. It was Limann’s betrayal of the commitment he made to pursue probity and accountability.

Dr Asamoah says, “Thus the long era of the PNDC began. It lasted almost 20 years!” It is surprising that, as a lawyer, the author makes no distinction between the just over 10 years of PNDC rule and the period after the 1992 constitution.

The author wrongly surmises that the exit of Chris Atim and Akata-Pore from the original composition of the PNDC was because they regretted having deposed a president of northern origin (i.e. Limann). They were “book” socialists with dangerously radical views likely to disrupt any effort to build an inclusive and participatory democracy.

It is also wrong to present the inclusion of Alhaji Mahama Iddrisu in the PNDC as simply due to his northern origin, without reference to his own qualities and experience.

Dr Asamoah claims, “I sometimes chaired cabinet meetings, particularly after the return to constitutional rule.”

This does not agree with my personal recollections. On assuming office at the Castle as Acting Director of the Castle Information Bureau I was directed to attend meetings of the Committee of Secretaries in order to fully inform the draft speeches, releases etc. which I had to prepare. After about a year, some PNDC Sector Secretaries complained to the Chairman of the Committee, P.V. Obeng, that they suspected me of being the source of numerous leaks from the meetings. Chairman Rawlings therefore directed I should rather attend PNDC meetings. (The cabinet leaks continued!)

Prior to 1984, I do not recall Dr Asamoah chairing a meeting. Between 1984 and 1993 I was not at these meetings and so I have no knowledge of whether Dr Asamoah chaired any meetings. However under the Fourth Republic I attended all Cabinet meetings from 1993 to 2000, except for a few absences due to illness or travel. I cannot recall any occasion when Dr Asamoah chaired a meeting. Mr Nathan Quao, as our resident ‘elder’, was often called upon, as were P.V. Obeng and Alhaji Mahama Iddrisu. The chair was not, as the author claims, elected by cabinet members, but delegated by the President. During the second NDC term in office, Cabinet was almost invariably chaired by Vice-President Mills. During the NDC’s first term, however, Vice President Arkaah was not called upon, as he never spoke but sat silently making copious notes in microscopic handwriting!

In discussing the cabinet system as it functioned during the PNDC period, the author omits mention of the introduction of Joint Meetings. Once each month, the regular cabinet meeting was enlarged to include the ten Regional Secretaries, together with the ten Regional Organising Assistants of the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDR). This was to counteract the old style top-down centralism of previous governments and to enable discussion of policies and proposed legislation to benefit from local and grassroots knowledge. It also enabled the regional representatives, on their return home, to explain to the people the rationale behind government decisions. The one time that the author mentions the Joint Meetings, it is in the context of planning the formation of the National Democratic Congress party in the early 1990s, when these meetings had long been a regular fixture.

The author gives a very superficial mention of the change from PDC/WDC to CDR, calling it a reorganisation of the PDC/WDC system but with no explanation of the reasons or the real nature of the changes made. One has the impression that the author had little regard for these organs and perhaps found them irritating! This attitude is hardly consistent with his statement that he has “always thought that these values could be best promoted by a revolutionary mass movement.”

The author discusses complaints from the JFM, the Daily Graphic and other sources about a lack of clear revolutionary strategy and economic policy, with all his examples coming from 1982. Then he goes on to say, “With the reliance of the PNDC on the IMF and the World Bank, economic policy was bound to be quite conventional.”

In 1982? In that year, Ghana was not only facing an empty treasury, thanks to the economic blunders of the Limann regime, as well as a suspension of oil shipments from Nigeria, but also a natural disaster of severe drought which caused food shortages and lowering of the Volta Lake and consequently a drastic cut in hydroelectricity. The 1982-83 dry season saw unprecedented bushfires, which destroyed huge areas of forest, cocoa farms and other assets, followed shortly by the expulsion of over one million Ghanaians from Nigeria. 1982 and part of 1983 was a time of crisis management.

Meanwhile, some of the more radical PNDC members were touring socialist countries seeking financial help. They returned with expressions of goodwill but little substantial help.

It was not until later in 1983 that an economic recovery plan was drawn up and presented to the IMF and World Bank. Note that this was not a mere “begging letter” but a detailed programme of necessary action.

It is worth noting that the response of both the international “donors” and bilateral donors was greatly influenced by the efficiency with which the PNDC had handled the drought crisis and especially the “returnees” from Nigeria. The world’s media had descended on Ghana expecting to film refugee camps and scenes of suffering. Instead they saw a precise and efficient operation, which received, registered, gave medical help and transported the returnees to their hometowns, despite the desperate lack of resources. As time went on, the terms of loans became more and more concessionary as the PNDC government demonstrated its efficient and effective utilisation of these funds. There was an increase in outright grants as the infrastructure and the economy improved.

Much is made of the conditionalities imposed by the lending agencies. Whilst many were irksome, the truth is that some of them, such as the redeployment of some government employees, would have had to be carried by the PNDC whether or not the lending agencies demanded them. I recall Alhaji Mahama Iddrisu, who had led a team to audit the government payroll, showing me some of the results. For example, the Agricultural Mechanisation Unit had about 200 tractor drivers, but only two tractors in good working order!

“In November 1984, the PNDC decided to rename the Defence Committees,” says Dr Asamoah. “Coordinators were redesignated Organising Assistants.” He also mentioned the appointment of Col J.Y. Assasie to head the organisation.

Changing names means very little, as we have seen with the change from Secondary Schools to High Schools! What matters is the substance, not the name, but Dr Asamoah says nothing about the substance of the changes, which gave clear and structured guidelines to the CDRs as well as practical responsibilities focussing on projects and programmes, dispute resolution, education, etc., under the guidance of a strict yet fatherly leader. Indeed Col. Assasie became so well loved that when he died, thousands of cadres made their way from all corners of the country to mourn him. Unlike the party activists of today who demand “allowances” for food and transport, the cadres brought with them yams, beans, corn, etc. from their own farms and many of them slept on the bare concrete outside the funeral venue.

Dr Asamoah says nothing about the good work done by the CDRs and I suspect that he did not like them. On one point he is downright hostile, saying that the Arbitration and Complaints Departments (ARBICOM) of the CDRs were “…unauthorised and oppressive ‘courts’”

Granted that a few maverick ARBICOMs had to be brought to order for overstepping their bounds, the great majority did a splendid job of resolving local disputes and complaints with common sense and sensitivity.

Dr Asamoah rightly points out that the well-worn phrase “Culture of Silence” was not the invention of Professor Adu Boahen, but was first used by Rawlings as early as 1984 at a rally in Conakry, Guinea. Indeed Chairman Rawlings used the phrase several times before 1984. However in the mid 1980s at a gathering of personnel of the then state-owned media he accused many of them of a self-imposed culture of silence. By avoiding anything at all controversial, they were producing dull, bland and uninteresting reportage. He asked them to be more lively, saying that there was nothing wrong with criticism so long as it was objective and that they should express opinions so long as they did not confuse opinion with fact.

Today, many of us may think that journalism has gone to the opposite extreme!

In reference to the People’s Shops which were set up in the early 1980s to ensure fair distribution of scarce “essential commodities”, the author says, “In the midst of scarcity, the People’s shops themselves became avenues of colossal corruption and fraud.” Yes there were some cases (though hardly “colossal”) but the PNDC put checks in place and imposed the same strict standards on its people that it expected from others. For example, a PNDC District Secretary in Techiman was removed from office for diverting a large part of the District’s allocation of flour to his wife, who was a baker. Even some District Secretaries who were entirely honest in their dealings but were unable to account for the goods which had passed through their hands due to lack of proper records were imprisoned for a time. The lesson was that honesty is not enough. Accountability means keeping accurate records – a lesson that many of today’s managers and institutions would do well to learn!

Throughout this book, Dr Asamoah often makes reference to the PNDC as a “military government” and the post-1992 period as “civilian government.”

Whilst it is true that the PNDC came into being through military action, there was a large civilian majority in the government structures at various levels. It is therefore inappropriate to refer to the post-1992 constitutional period as “the civilian government.”

Dr Asamoah appears to take credit for many new laws and law reforms, which were in fact generated and driven by PNDCL 42 (which forms the core of the Directive Principles of State Policy in the 1992 Constitution). In presenting these laws to Cabinet, he was simply doing his job. Indeed, at Cabinet meetings at which proposed Bills relating to sensitive gender issues, widowhood, inheritance, rape etc. were being discussed, he could sometimes be heard making chauvinistic asides, which could cast doubt on his sincerity about the issues. Even if he (and one or two of his colleagues) were joking, such remarks were inappropriate and also offensive to the women present!

Dr Asamoah is remarkably brief in recounting what is probably one of the most significant achievements of the PNDC – the participatory process through elective local government to national constitutional rule.

He describes the National Commission for Democracy, under the leadership of Justice D.F. Annan, holding a 3-day national seminar on True Democracy in Ghana in 1987, he then jumps to the launching of the “Blue Book” setting out a draft plan for local government.

So what happened between these two events?

Thousands of Ghanaians from all walks of life throughout the country took part in public fora in the regions and districts at which they could express their opinions on the type of governance they wished to see at the local level. It was the NCD’s job to collect and collate all these ideas. Areas of widespread common ground included the wish to have more Districts and more electoral areas within each District so that more people would have the opportunity to participate in the governance of their areas, and the desire to reduce the cost of campaigning by having the NCD or the Electoral Commission bear the cost of printing posters and mounting common platforms at which all the candidates could interact with the public. This last measure was to prevent wealthy candidates from having an advantage. There was also widespread agreement that District Assemblies, in addition to raising revenue locally, should have certain revenues ceded to them so that they could initiate more local development projects.

A team was set up to distil this information into the “Blue Book”, which was then sent back to the people for comments and suggested amendments before the drafting of what was to become the local government law of 1988. This meant that the new District Assemblies were not simply handed down from above. The people felt a sense of ownership because they had played a part in shaping the new system.

Dr Asamoah says nothing about this. He simply jumps to “Following the establishment of the District Assemblies…” He also has nothing to say about the surge of local pride and initiative, which followed the establishment of the Assemblies.

Dr Asamoah gives a similarly sketchy account of the next step from local to national constitutional governance. He does mention the new round of public fora organised by the NCD to discuss the form which this should take, and the fact that results were then given to a panel of independent constitutional experts who were to produce a preliminary draft constitution. The panel’s report and draft then went to the PNDC and then a Consultative Assembly made up of representatives of all identifiable bodies from professional bodies to Trades Unions, farmers etc. etc. (The Ghana Bar Association boycotted the exercise, resenting the inclusion of so many lay people.) As with the Local Government Law, the new constitution was shaped by the input of thousands of ordinary Ghanaians, in the spirit of participatory democracy, rather than being handed down by a small clique of experts. Finally, a referendum was held to give the people the opportunity to give the final seal of approval. As soon as the constitution was promulgated on 7 January 1992, the formation of political parties began and preparations were made for elections.

Whilst the author says that Rawlings expressed misgivings about the dangers of party politics (and time has shown that these dangers are very real!), he does not mention that the very same misgivings were expressed in the report of the panel of constitutional experts, who suggested that one way of reducing the “winner takes all” effect of party politics would be to introduce some form of proportional representation. However, this is a rather complex system which would have required a great deal of public education which could not have been possible within the timetable already announced for the return of constitutional rule.

Dr Asamoah says, “I had always lamented the absence of camaraderie in the party (NDC)” and “There was no club house, for example, where members of the party could socialise.”

I do not think that NDC members wanted an exclusive whisky club for the party “elite”. In my experience, there was plenty of camaraderie of a more democratic kind at which NDC people of all shades got together, not in some special clubhouse but wherever they happened to be.

The author says that he declined to attend a few days military training exercise organised to enable new ministerial appointees to get to know the old ones. This was an exercise in team building and camaraderie and was effective and also great fun! Perhaps the author feared for his dignity?

The book mentions the investigations made by CHRAJ into allegations made in the opposition press against some Ministers, especially reports that they had acquired numerous properties. The papers illustrated their articles with photographs, often fake. For example, one showed what purported to be Col. Osei Wusu’s “mansion” at Haatso. It did indeed show the Colonel’s garden wall and the tops of some trees which he had planted around his modest bungalow, but the massive “mansion” was a large building on a plot adjacent to his, and belonged to someone else!

Considering that the author tells us he was a prominent member of the “Special Committee” set up to do some “damage control” to counter these allegations of corruption by devising the strategy of referring the allegations to CHRAJ and then, where any allegation was shown to be untrue, encouraging the Minister concerned to sue the newspaper for libel, his account of the episode does not clear the air at all, nor does it clear the good names of the innocent.

Dr Isaac Adjei Marfo, for example was accused of owning many properties, the majority of which were found to be family houses, one of which was put up by contributions from the Marfo brothers for their mother. The adverse finding by CHRAJ was that he had not fully paid income tax on the profits from his farm, a matter which was not part of the press allegation. Why did the Special Committee not encourage him to sue the publication, which had libelled him, after paying his tax arrears?

In the case of Col Osei Wusu, once family properties were excluded as well as his Kumasi house built when he was MD of Paramount Distilleries, CHRAJ turned its attention to his Haatso “Mansion”, built by direct labour under his supervision. The cost which he gave was then compared to that of an independent valuer, who gave ¢30,000,000 more than the Minister had declared, according to CHRAJ’s report. Later, CHRAJ discovered that a typing error had one nought too many, and the actual discrepancy was only 3 million, an amount which could not cover the value of the Colonel’s work as self-builder and supervisor! Where the author gets the figure ¢18 million in his present account I do not know because he did not mention it when reporting on the case to Cabinet.

I went to visit Col. Osei Wusu at his little “mansion” and urged him to sue the newspaper. I am glad to learn that he did, eventually, go to court, but why did the author not tell us the outcome?

CHRAJ stated that it found no evidence that Ibrahim Adam and others benefited in any in any way from their decision to waive taxes and duties on some fishing companies. In the face of a national fish shortage, their decision may be regarded as an error of judgement, but was certainly not corruption.

Curiously, the author does not mention the famous so-called “white paper” which is used even today to malign President Rawlings with accusations that he was trying to save “guilty” people. I attended the Cabinet meeting at which the author presented the CHRAJ report on the first batch of alleged corrupt ministers. He went through it in detail and I was directed to prepare a release from my office giving those details. This was not a White Paper. White Papers convey decisions of government and this release merely summarised the CHRAJ report with some observations by the Attorney General.

It is hardly surprising that several of the Ministers concerned resigned, because the “Special Committee” did not carry through the strategy which it had planned. When many newspapers greeted the CHRAJ report with bold headlines such as ADVERSE FINDINGS, MINISTERS GUILTY, etc., why did the relevant members of the Special Committee not respond with a clear message that the allegations published in the newspapers had NOT been substantiated and that those concerned would be taking legal action? The few adverse findings such as under-declared tax liabilities were secondary to the original accusations of corruption.

One would have hoped that the author would have taken the opportunity to clarify these matters.

The author refers to the “brawl” between President Rawlings and Vice President Arkaah.

From the time Arkaah attended the first Cabinet meeting after the 1992 elections until his undignified exit in 1996, I never saw him interact with anyone else, whether as friend or colleague or in the course of business. He would sit in silence, not contributing to discussions whilst writing copious notes in tiny handwriting, with one arm protectively around his papers like a schoolboy trying to prevent his neighbours from copying.

At the Cabinet meeting immediately following his public declaration of defection from the government, I arrived early. A few early Cabinet members were discussing what to do if Arkaah turned up, since common decency demanded that if he had rejected the government he must resign his Vice-Presidency. As more Cabinet members arrived, some said, “If Arkaah comes, we should all walk out.” Another said, “Why? We are the ones with the right to be here. We should rather tell Arkaah to walk out!”

Arkaah came in, walked silently to his usual place and sat down. None of the Ministers, who only a moment ago were discussing what to do, did or said anything!

Then President Rawlings arrived. I was seated about six feet behind and to the right of Arkaah, so I had a good view of what happened next. The President grasped Arkaah’s left upper arm, intending to walk him out of the room. Arkaah stood up, knocking over his chair, and tried to twist himself out of the President’s grip. The two men tripped over the chair and fell to the ground. Commodore Steve Obimpeh stepped up to cool tempers. Arkaah got up and walked out, loudly announcing that he was going directly from the Castle to complain to the Police and the press that he had been brutally assaulted.

His very public version of what had taken place was not accurate. He alleged that the President had come behind his chair and struck him a heavy blow, which would have been impossible since the Cabinet chairs had high solid backs, unless he had been struck on the head! He also had published in the press a photograph of damage done to his jacket. Even if he had tampered with the jacket before taking the photograph, the minor damage done to the shoulder seam is not inconsistent with someone twisting his body to escape a strong grip around his upper arm.

The author makes a rather surprising statement about the 2000 elections: “the decision to support sitting Members of Parliament as candidates proved counter productive and contributed to our defeat.”

Many NDC members blame Dr Asamoah for this decision. By his own admission, he had become what might be called the “election guru”.

Some sitting MPs had become unpopular in their constituencies, and their constituents deluged the Castle and the Party HQ with complaints, suggestions of sound and popular prospective candidates and warning of disaster if their concerns were not heeded. Unfortunately, most of these warning were not heeded and because Dr Asamoah had been so deeply involved in organising previous elections and was the de facto “treasurer” of the election funds he was perceived by many in the NDC for being to blame for retaining unsuitable candidates in some constituencies.

Dr Asamoah gives the impression that he was singled out for heckling and rowdy behaviour by NPP hooligans at the State House at the first part of the handover ceremony from Rawlings to Kufuor.

The fact is that a rowdy mob of NPP fans had occupied all the chairs provided for a limited audience. They drove away with jeers and insults anyone perceived to have NDC connections, whilst State Protocol staff and NPP officials looked on. What should have been a dignified ceremony of significance to all citizens was cheapened and mocked.

As I attempted to enter the venue, I witnessed the most disgraceful incident of all. I saw Dr Afari Gyan, the Electoral Commissioner and his wife looking upset. When I asked what was the matter, he said the hooligans had told him that there was no seat for him and that he should go away! This was the man whose hard work and fair play had made the NPP victory possible!

Dr Asamoah makes reference to the attempted criminal prosecution of Mpianim, Kufuor’s Chief of Staff and the organisers of the “Ghana @ 50” celebrations. He agrees that Mr Justice Marful-Sau had no option but to say that he had no jurisdiction. But whose fault was it?

Who drafted the legal terms of reference of the Commission which investigated the financial malfeasance in such a way that those who were guilty were protected from prosecution? Presumably the Attorney General’s office and/or some legal advisors at the Castle. And then, these same people prepared a case for prosecution. Is it credible to believe that they did not realise that the case must fail?

Marful-Sau did his National Service in my office and proved himself to be a young lawyer of the highest integrity. It must have taken considerable moral courage to rule on the Mpianim case, and he in no way deserves the criticisms launched by many NDC observers.

The author refers to allegations of election rigging in the Tain constituency in 2008. That election must have witnessed the greatest number of TV, press and radio teams and observers ever concentrated in one small constituency! It is hard to see how anything could have escaped this level of scrutiny!

Appendix I covers at length Dr Asamoah’s defence of Captain Kojo Tsikata at Kufuor’s “Reconciliation Commission”. One would think that, as a distinguished lawyer, the author would have done us the favour of a more wide-ranging analysis of the Commission’s proceedings, rather than focussing on only one case.

The author says, “President Rawlings, in his usual Machiavellian way…” When Rawlings strategizes, it is Machiavellian, but when Dr Asamoah strategizes, it shows what an astute politician he is!

Dr Asamoah can be quick to point out the inconsistencies of others, but he has devised a defence for any inconsistency on his part by stating, “I am essentially a freethinker defying stereotyping.” Enough said!

Source: JJR WordPress

Dany Laferrière: the one who plays with words

Dany Laferrière: the one who plays with words

A Haitian writer and citizen of Quebec has been awarded the International Literature Prize by Berlin-based House of World Cultures. He achieved fame with his provocative writing on racism and sex.

When asked about the whereabouts of his "true" hometown, Dany Laferrière doesn't need to give much thought to his answer: "Berlin - but only for four days." He smiles. Born in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince as Windsor Kléber Laferrière on April 13, 1953, Laferrière (who is now 61) grew up in the town of Petit Goave, equally in Haiti. But he feels at home just about everywhere in the world.

At the age of 23, he fled the regime of former dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier, commonly known as Baby Doc, to live in Montreal, Quebec. Later he spent time in Miami, to return to Montreal in 2002 where his wife and children have made their home."My own home is in airplanes," he says. The author travels extensively in order to present his works around the world. "Of course I miss my family. But I love meeting people from other countries. And I love learning new things."

For now, that's a stopover in Berlin, where Laferrière was awarded this year's International Literature Prize by the Berlin-based House of World Cultures on Thursday (03.06.2014), for his novel "The Return" (L'enigme du retour). This is the only work of his which so far has been translated into German - which is why, so far, Laferière is hardly known in Germany.

For now, that's a stopover in Berlin, where Laferrière was awarded this year's International Literature Prize by the Berlin-based House of World Cultures on Thursday (03.06.2014), for his novel "The Return" (L'enigme du retour). This is the only work of his which so far has been translated into German - which is why, so far, Laferière is hardly known in Germany.

"We went for it because it's a highly personal book," explains Sabine Peschel of DW, who is also a member of the jury."It's all about loss, death, confrontation; life in its most basic, naked form."

And it's about homeland. Laferrière describes his return to his native country following the death of his father, who went into exile when the author was only four years old. Laferrière travels to Port-au-Prince in order to inform his mother that her husband has passed away. And although Laferrière had never developed a close relationship to his father, he now follows the elder Laferrière's footsteps all the way to his place of birth while getting in touch with old friends of his father.

But during this trip, Laferrière also becomes aware of his total alienation from his home country after having spent 30 years in exile. Now and again, the narration switches from prose to poetry, expressing its own peculiar style - yet another reason the jury picked it.

The first book – a second birthday

"Everything in the book is true. It's like a photograph of the situation in Port-au-Prince. Perhaps not all the details really took place on precisely these dates, but the details in themselves are absolutely true," says Laferrière. And yet, he adds, the book does not really recount his life, but rather the history of Haitians who, like him, fled the impoverished country.

Tough challenges awaited Laferrière in Montreal. For years, it was difficult for him to make ends meet. The breakthrough came with the publication of first work "How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired" (Comment faire l'amour avec un nègre sans se fatiguer) in 1985.

Tough challenges awaited Laferrière in Montreal. For years, it was difficult for him to make ends meet. The breakthrough came with the publication of first work "How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired" (Comment faire l'amour avec un nègre sans se fatiguer) in 1985.

"This was almost like my second birthday," he remembers. The book was quite successful. "I always hoped that one day, a girl would say to me: Hey, are you the author of this book? As though I were a rockstar." Nowadays, Lafferière laughs about his yearning for fame in his youth. "Ultimately, one writes because one happens to be a writer."

Following this first success, Laferrière continued to produce works heavily focusing on topics such as discrimination, racism and sex. A particular milestone in his career was the movie "Heading South" (Vers le Sud) starring Charlotte Rampling, which was adapted from three of his short stories. It's about old white women travelling to African countries in the search for young black lovers.

Laferrière writes exclusively in French, and he is the first Haitian and the first citizen of Quebec who was nominated as a member of the French language watchdog Académie Francaise.

Some of his works have been translated into English. But so far, only "The Return" - for which he received the award in Berlin - has been translated into German. He hopes that the award will produce more interest in his works in Germany.

He does not, however, intend to turn the world into a better place, he says: "I am a writer, simply because I love playing with words. No, I do not want to too much responsibility ascribe to my poor little scribblings."

Date 03.07.2014

Author Susanne Dickel / ad

Editor Sonya Diehn

Source: Deutsche Welle

Horrors of War in ‘A Long Long Way’

Horrors of War in ‘A Long Long Way’

The Plot synopsis

A Book Review [1]: “The young protagonist Willie Dunne leaves Dublin to fight voluntarily for the Allies as a member of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, leaving behind his prospective bride Gretta and his policeman father. He is caught between the warfare playing out on foreign fields (mainly at Flanders) and that festering at home, waiting to erupt with the Easter Rising. The novel was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2005. In a 2009 US National Public Radio interview, author R. L. Stine stated that A Long Long Way was one of the most beautifully written books he had ever read, and gave copies of the novel to friends and family to read.” In this edition, Esi Asantewaa takes a second look at the book.

The Review

Barry presents Horrors of War in ‘A Long Long Way’ through techniques such as: Chremamorphism. The effect of this method involves the soldiers being dehumanised. Another method used is language in letters- this gives readers an insight on the relationship between the characters which exposed the characters, thoughts and feelings during the war. In addition to these were prolonged sentences which illustrate the never ending horrors of war. Linking these to the context of horrors of war; Barry creates a character of his own Irish Descent. Presumably, this is to relive or recount soldiers’ war memories.

On Page 290, we see the last letter being sent to Willie from his Dad. The dad started the letter with the phrase: ‘My dear Son’ (p. 290). The use of language shows the respect Willie’s Dad has towards him. The effect this has on the reader is the sense of love and warmth between father and son. It could also be suggested that the last letter signifies the end of the loving relationship and how War in particular wrecked it. In addition to this, it could be suggested that perhaps the last letter where Willie’s Dad pours out his heart to Willie gives the impression that the War was not as bad as it seemed for Willie. Presumably, this is due to the fact that Willie’s dad was supportive during the difficult times of his life.

The sincerity and honesty really reveal their close relationship. It almost seems that the war and horrors have drawn them closer. Once again, the effect this has on readers is the feeling of optimism that we share with Willie’s Dad as well as the happiness and relief when Willie returns home. The exchanged letters between both parties illustrate the growing bond between the two, and how it developed during the war especially the last letter, in my opinion, signifies the reinforcing love between Willie and his dad. The three words ‘My dear Son’ (p.290), illustrates the tone of love and respect towards his son. It also suggests how immensely Willie’s dad was proud of his courage. Photo Reporting: Horrors of War in ‘A Long Long Way’

Not only does Willie represent a soldier fighting for his country but he is also seen as a true Hero for his Dad and his family. The last letter sent leads was followed by the aftermath of the War. Page ‘182’ shows us a long sentence. This is used to illustrate horrors of war. Arguably ‘Surely no man’ (p. 182) signifies the nightmare of the guns and the environmental change as well as how the mentality of the soldiers changed due to the likely effect of the good range of guns and the psychological effect [mentality of each for himself] it might have had on the movements of the soldiers in their trenches.

Not only does Willie represent a soldier fighting for his country but he is also seen as a true Hero for his Dad and his family. The last letter sent leads was followed by the aftermath of the War. Page ‘182’ shows us a long sentence. This is used to illustrate horrors of war. Arguably ‘Surely no man’ (p. 182) signifies the nightmare of the guns and the environmental change as well as how the mentality of the soldiers changed due to the likely effect of the good range of guns and the psychological effect [mentality of each for himself] it might have had on the movements of the soldiers in their trenches.

It could be suggested that due to the effect of the guns mentioned in the paragraph above, the reader can expect the intensity of the war. With the horrible pulverising effect of the guns on the opposing forces, the reader could imagine the stream of consciousness that the soldiers might have gone through and how secure and confident they now feel in their trenches as the enemy forces could hardly leap. They could only think of what would happen to them the as situation change against them. I believe this shows the effect of the reader’s sympathetic feelings towards the soldiers who faced life and death situations. The sentence length and the descriptive words capture this atmosphere.

From this perspective, I personally believe that the prolonged sentence signifies the extreme violence that took place as soon as the weapon was used. I also believe that perhaps, Barry is using the guns and other weapons as the blame for the whole war itself. Arguably, without these weapons the fellow men and soldiers would be powerless. Barry employs long sentences, active verbs, adjective and adverbs to create a scene of bombardment and how powerful warring soldier or armies can become under the influence of different weapons at their disposal.

In the last but one paragraph of page 29, Barry used chremamorphism such as ‘beetroots rotting,’ to present horrors of war in relation to the death of some of the young and probably inexperienced soldiers like himself all in the spirit of patriotism. The impression created in this paragraph to the reader is that some of the dead and wounded soldiers were not evacuated and were left to die in their wounds on the battlefield or were made to feel like waste and probably, of no use to their country. Barry makes this comparative observation putting himself in that unfortunate trauma and in vocabularies or jargons that might probably not be readily understood by the foreign reader.

On Page 121 of the last but one paragraph, Barry evokes these words: ‘dead were tidied ‘. I believe that Barry used this short sentence length to create a scenery atmosphere that represents an emotional horror of war. This also signifies non-existent tribute to soldiers that have passed away and for whatever reasons, their dead bodies left uncovered or not attended to for a while. By the use of these words, the reader might have been tempted to conclude that the tidying bodies of the dead soldiers could hardly be identified by the surviving families or warring soldier. It is unclear whether there was any form of memorial or remembrance for them. The words ‘dead were tidied’ could however, mean a mass-burial which appears to me as the most symbolic exposition of the reality of the title of the book.

In conclusion, I believe that Barry leaves an emotional impact on his readers by using different types of techniques such as the form of language and structure to present the horrors of war. Above all, Barry left moved his readers with most significant thing- which I believed were the letters to give an insight into how the characters in his account coped during and after the war and the never ending horrors.

I recommend A Long Long Way as a must read book.

Reviewed By Esi Asantewaa. Esi is a Sub-Youth-Editor at JusticeGhana

….

A Long Long Way is a novel by Irish author Sebastian Barry, set during the First World War. Wikipedia

Published: February 3, 2005

Author: Sebastian Barry

Genres: Fiction, Novel

Nominations: Man Booker Prize, International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award

Reference

[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Long_Long_Way

JusticeGhana

Nigerian-German learns 'Schindler's List' killer was her grandfather

Nigerian-German learns 'Schindler's List' killer was her grandfather

A steel-eyed Nazi killer picks off Jewish prisoners with a rifle from a balcony in a concentration camp in 1944.

More than six decades later, a Nigerian-German woman who has studied in Israel thumbs through a book about the sniper and is shocked to learn the man is her own grandfather.

In a memoir published this month with the chilling title "Amon: My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me", Jennifer Teege recounts her dark family secret and the extraordinary story of how her own life became enmeshed with one of history's grimmest chapters.

{sidebar id=10 align=right}Teege is the child of a Nigerian student and the German daughter of Amon Goeth, the commandant of the Plaszow concentration camp outside Krakow in today's Poland who featured in Steven Spielberg's 1993 Holocaust drama "Schindler's List".

[On This Day: Boy Scout leads most audacious escape from Auschwitz]

The 43-year-old Teege learned only by chance five years ago that her grandfather was the sadist known as the "Butcher of Plaszow", who was hanged in 1946 for the torture and murder of thousands of victims.

Teege's parents had only a brief affair and gave her away to a children's home weeks after her birth. She was placed with a foster family and eventually adopted by a well-off couple in a Munich suburb when she was seven, seeing her biological mother only sporadically.

Half a lifetime later, looking through the stacks of her local library in the northern city of Hamburg, she stumbled upon a title that resonated with her own fractured personal history: "Ich muss doch meinen Vater lieben, oder?" (I Have to Love My Father, Right?).

The middle-aged woman pictured on the book's sleeve looked faintly familiar and a quick scan of the biographical details revealed a perfect match with those of her birth mother.

"It was like the carpet was ripped out beneath my feet," Teege told AFP.

"I had to go lie down on a bench. I called my husband and told him I couldn't drive and needed to be picked up. Then I said to my family that I did not want to be disturbed, went to bed and read the book cover to cover."

In one of the most harrowing scenes of Spielberg's film, Goeth as played by Ralph Fiennes begins shooting Jewish captives for sport from the balcony of his camp villa before letting his dogs rip them limb from limb.

[30 Auschwitz guards to face criminal probes: Germany]

Teege said she had seen "Schindler's List" while living as a student in Israel but was uncertain how true-to-life its portrayal of Goeth was.

"And I drew no connection with my own life. Even though my birth name is Goeth, it wasn't written out on the screen so when I heard it in the film it didn't even occur to me that there could be a link."

A picture of Goeth above the bed

Even after her parents gave her up, Teege had fond memories of her grandmother Ruth's occasional visits and cards on her birthday.

"As an abandoned child, she was a very important person in my life," she said.

Teege was shattered to learn later that this kindly woman had lived for a time with Goeth as his lover in the same camp villa from which he savagely murdered prisoners.

They met while she was working as a secretary for Schindler in Krakow. Their daughter Monika was born in 1945.

Ruth took Goeth's name shortly after his execution and, denying his crimes to the end, still had a picture of him hanging above her bed when she committed suicide in 1983.

[On This Day: Jesse Owens snubbed by Hitler after claiming Olympic glory]

An advertising copywriter and mother of two, Teege exudes a warmth that belies her bloodline.

Her book, co-written with journalist Nikola Sellmair, features a portrait of the light-skinned black Teege gazing out from the cover.

The title refers to her realisation that her own grandfather would have seen her as subhuman like the Jews he slaughtered.

Teege herself has visited the Schindler museum in Krakow, the Goeth villa at Plaszow and laid flowers for his victims at the camp memorial.

Although she and her mother are estranged, she says she can understand why the terrible secrets were kept from her, noting that the second generation of Germans after the Nazis had a very different burden to bear than the third.

"My mother was absolutely unable to cope with her own history. And she wanted to protect me by keeping me in the dark about it," she said.

"Once I learned about my family's past, I had to make a conscious decision to live in the here and now."

Teege said she aimed by means of the book to work through the horror and depression that her family tree inspired, but also to ask more universal questions about how to deal with the weight of the past on the present.

"Of course my story is gripping and original," she said.

"But it's also more generally about the fact that it's possible to move beyond repression to gain a kind of personal freedom from the past by finding out who you really are."

Teege said her middle-class upbringing had largely shielded her from racism in today's Germany.

Now, after wrestling with her mother's heritage for so long, she is ready to begin exploring her paternal African roots.

"I'm looking forward to learning more about my other side."

Source: AFP By Deborah Cole | AFP – Thu, Oct 3, 2013